April 30,

2010

GUEST EDITORIAL

The

school

board's wrongful assumptions

By PAUL AUGROS |

Because the school district operating budget is nearly twice that of the town, it is the source of a great deal of debate and contention.

The school budget recommended by the Budget Committee for 2010-2011

and passed by the voters in March was $35.6

million. This represents an increase of roughly $1 million over 2009-2010.

At the February 1st school board meeting, members of the board proposed a further increase to this number of roughly $1 million, an effort which the voters present defeated.

A subsequent motion by a member of the Budget Committee sought to reduce the proposed budget to be the same as the current budget.

This motion also failed, guaranteeing a very large property tax increase this coming

year.

It is my opinion that no organization should be so insulated from economic realities that its budget continues to increase even in a year in which the businesses and individuals who fund it are facing steep cuts.

Many districts elsewhere are taking decisive steps to reduce spending in response to the recession, including staff reductions, furloughs, reductions or eliminations of departments such as guidance, physical education, arts and extra-curricular activities.

There was much debating around the margins at the Feb 1st meeting; I believe, however, that the disagreement is more fundamental in nature, and I challenge some core assumptions that were not directly discussed.

The arguments at the meeting from those in favor of greater spending generally arose from one of two unspoken assumptions, which I will address below.

Assumption #1: Any decrease in spending (or smaller increases, as the case may be) would be detrimental to the education of our children.

Some proponents of this argument were calm and reasoned; others adopted a condescending tone, and impugned the motives of their opponents while claiming a monopoly on concern for children.

Of course schools need money to function. For the above assumption to be true without qualification, however (and there were no qualifications offered), a direct correlation between spending and student performance would have to be established.

Furthermore, it must be demonstrated that this correlation exists at all rates of spending; that it does not abide the law of diminishing returns.

I assert that no such correlation exists.

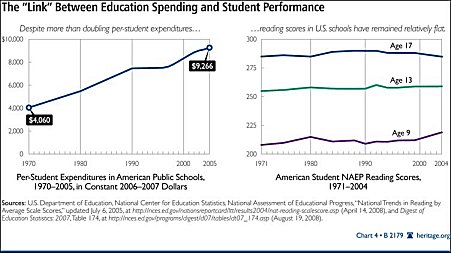

The chart below (click the image to enlarge), from a Heritage Foundation article on education spending, compares spending (inflation-adjusted) with reading performance. In comparing the various rates of performance versus spending, one sees no more evidence of a positive correlation than of an inverse correlation, indicating that spending and performance are not related at all, much less that they are related at all levels of spending.

(Click

image to enlarge)

(Click image to

enlarge)

Nevertheless, one could argue that even if increases in average spending do not improve performance, it is possible that districts with higher spending generally produce better results than those with less.

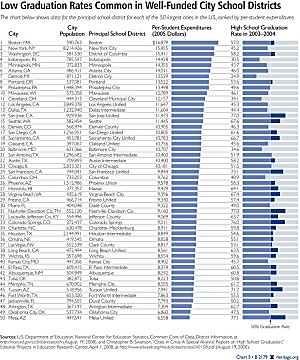

The data in the second chart (click the image to enlarge), however, do not support this theory.

High and low graduation rates are scattered throughout, and the best graduation rates are generally not found among the highest spending districts.

(Click

image to enlarge)

(Click

image to enlarge)

A wide array of factors can affect student performance and graduation rates, from cultural environment, to teacher incentives and school competition.

Spending, however, does not appear to have a prominent place on the list.

Undoubtedly, performance would suffer at some point if spending were continually to decrease.

But I think it is important to stress that we don't know what that point is, because we have never spent anywhere near it, and spending has been always increasing.

More spending won't necessarily improve our schools, but it will increase taxes.

This year especially, we must break free of the mentality that says fiscal responsibility and quality education are mutually exclusive.

In exhorting us to spend more, many speak about what our duty to our children and community requires of us.

I am as strong an advocate as any for involvement, investment and sacrifice in service of the greater good of our children and community. This does not mean, though, that we ought to forge ahead with spending increases year after year, absent any evidence of its efficacy.

Such a policy does a service to no one. Children do not mandate a particular tax rate. In my experience, if children mandate anything, it is responsibility.

To that end, let us set an example for our children by practicing spending restraint and fiscal responsibility.

Assumption #2:

We can't be spending too much (or increasing spending too quickly) if we spend less than the state

average.

In light of the information above, this argument evaporates.

This assumption presupposes that state (and, for that matter

U.S.) spending averages are not already well above what is required for a good education.

Citing overspending elsewhere does not justify overspending here.

A member of the school board said at the meeting that "we have a business to run," and that a school is "just like a business." That may be true of a private school, which must offer a quality service at a competitive price or else go out of business.

But rather than generating revenue based on its merits, a government school consumes revenue raised by taxes, which residents are compelled to pay.

An entity of this sort, which cannot go out of business no matter how it is run, is fundamentally not a business. And a business that mistakenly overcharges for its services by 8%, as the district did this year, would not stay in business very long.

The duty to be frugal with other people's money does not require attention only when the stakes are high; it requires a consistency even in small matters, so as to continually assure taxpayers that the value of their money is understood by those tasked with divesting them of it.

|